Poetry is Power

When I tell my seventh-grade students we’re reading poetry, their response is usually the same: one long, collective groan. I try not to let it get to me, but it’s still disheartening. Their unenthusiastic reaction is similar to the response I hear from adults when words like “sonnet” and “figurative language” are thrown around.

My parents tell me they both took poetry classes but couldn’t understand what the teacher wanted. “I could never get out of it what the teacher got out of it,” my mom says, “so he’d give me a bad grade.”

Reading poetry can feel like a guessing or mind-reading game where students don’t even try to understand the poem because they're so focused on trying to understand what the teacher wants. This attitude extends beyond the classroom. Adults who don’t immediately understand a poem’s supposed “deeper meaning” can feel dumb or like they’re just not “artsy” enough to get it.

Unfortunately, there’s foundation for apprehension toward poetry and writing in general. In his book A Teaching Subject: Composition Since 1966, Joseph Harris overviews how composition courses have been taught since (surprise, surprise) 1966. Sometimes English teachers have focused more on grammar than content and more on product (the result) than on process (how to get the result). This can lead to teachers covering students’ papers in the dreaded red marks and students feeling that writing (and writing poetry in particular) is subjective. Harris’s book mostly focuses on composition courses instead of creative writing courses, which would more often include poetry. However, I think it’s safe to assume some pedagogical practices from composition instructors bled into the pedagogical practices of creative writing instructors because often teachers of the latter also teach the former.

Students can feel that what constitutes as “good” is merely up to the whims of the teacher. Admittedly, this is partially true. Poetry is an art and, like most art, is amorphous and difficult to define, so when a teacher grades poetry or a poetic analysis, the grade will depend on the teacher’s understanding of and definition of “good” poetry. Fortunately, a good teacher will define her expectations early on. It’s a little more complicated when it comes to published poetry. If you want to publish poetry, you should read poetry that’s currently being published. That will give you an idea as to what’s acceptable. Ultimately, my point is that poetry is and is not subjective. There are expectations and standards for poetry but those expectations are up to the teacher and/or publisher. It’s up to the poet to discover and understand those expectations.

The good news is you don’t have to be particularly clever or artistic to understand and, more importantly, to enjoy poetry. This is noteworthy because poetry can give meaning to the mundane. It can inspire, deepen understanding, and breed empathy and compassion. Poetry can do all the things we hope art will do: capture what it means to be human and give purpose for and to humanity.

How to Read Poetry

It took me until my master’s program to really understand that poetry is meant to be enjoyed as much as a good movie, painting, or culinary dish. In my program, I was lucky enough to work with Michael Lavers, a poet at BYU and author of After Earth, as he constructed his intro creative writing class. Lavers gave his students four steps to understanding and enjoying poetry. I’m only going to list three of them here as I think it’s safe to combine two. These steps are by no means all-inclusive, but for the poetic newbie, they can be helpful.

1. Ignore, for as long as you want, what the poem “means”

Archibald Macleish wrote, “A poem should not mean / But be.”

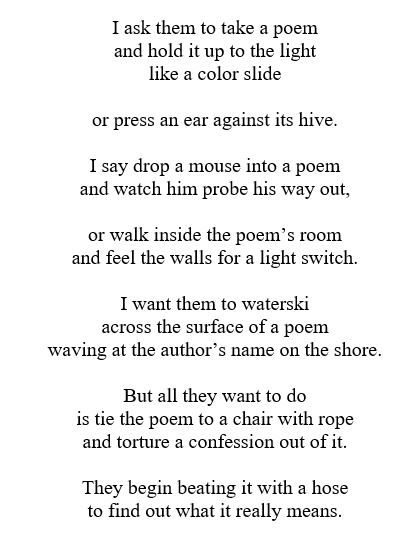

So often we forget that poetry is meant to be enjoyed that we skip right to “but what does it really mean?” In his “Introduction to Poetry,” Billy Collins writes,

Notice how Collins instructs his students to enjoy the sounds, images, and feelings the poem evokes. Poems are meant to be enjoyed. Read it and let yourself react however you react even if your first reaction is confusion.

2. Notice how musical the poem is

Poems are meant to be read out loud. Often multiple times.

Luckily, poetry can be short, which allows the reader time to sit with the poem. Read it multiple times. Highlight passages you love or confuse you. Look up words you don’t know. Look up words you do know. (You’ll be surprised how many double meanings sneak in there.)

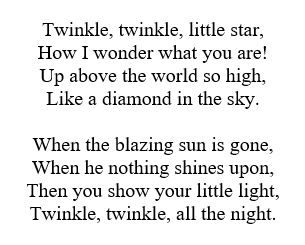

While reading the poem out loud, notice how rhythmic it feels. You inherently know when a poem has rhythm. You’ve been taught this your whole life. Read the following two stanzas from a poem by Jane Taylor and try not to sing! This familiar poem has an inherent rhythm—no additional music needed.

Go on, read it out loud.

Seriously.

3. Notice how poems appeal to the five senses

Poems (like most creative literature) appeal to our sense of smell, sight, touch, taste, and hearing. The poet Federico Garcia Lorca wrote, “A poet must be a professor of the five senses...”

When I first approach a poem, I often think of Vladimir Nabokov, a famous poet and essayist, who described the inspiration for his first poem in his book Speak, Memory.

A moment later my first poem began. What touched it off? I think I know. Without any wind blowing, the sheer weight of a raindrop, shining in parasitic luxury on a cordate leaf, caused its tip to dip, and what looked like a globule of quicksilver performed a sudden glissando down the center vein…

What was his inspiration? Watching a raindrop fall off a leaf.

Nabokov did not necessarily begin his poem with an idea to impart grand ideals or high-minded wisdom. (Whether or not he in fact did impart grand ideals or high-minded wisdom is another matter.) The point being poets often get at the general through the specific. When reading, focus on the specific (language that appeals to the five senses) then the general (“deeper meaning”) will come.

The Power of Poetry

All this talk of how to approach poetry naturally leads to one important question: So what? Why read poetry in the first place?

The best answer to that is, of course, a poem, specifically “The Hill We Climb,” written and presented by Amanda Gorman this year at President Biden’s inauguration.

At twenty-two, Gorman is the youngest poet to present at an inauguration, but she is far from inexperienced. According to People Magazine, Gorman is a former (and the first) national youth poet laureate, a graduate from Harvard, and the author of a forthcoming book Change Sings. A PBS interview with Gorman reveals that, as a child, she had a speech impediment, which she overcame and “at sixteen started her own youth literacy program, One Pen One Page.”

She told the interviewer, “The power of poetry is everything for me. Poetry is an artform, but to me, it’s also a weapon. It’s also an instrument. It’s the ability to make ideas that have been known, felt and said, and that’s a real . . . type of duty for the poet.”

Calling poetry “a weapon” makes it sound dangerous, hurtful, and striking. And it can be—in a positive, productive way. Poetry can change the way people feel and think about themselves, each other, and their environment. It can be a defense—a way to make others hear and understand your story. It’s also, as Gorman says, an instrument or a mode of storytelling and communicating.

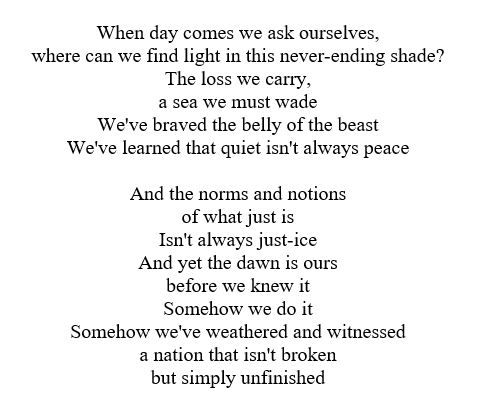

With this in mind, let’s dive into “The Hill We Climb.” Observe how this poem begins by contrasting light with dark.

Did you read it out loud?

Did you notice the rhythm created by the rhymes and repetition? Did you notice the concrete language (light, shade, wade, dawn, weathered, and witnessed)? What’s most striking about this poem, though, is the contrast between words and ideas: light vs. shade, quiet vs. peace, just-ice vs. just is, broken vs. unfinished.

We don’t need to worry about meaning right now, but I think it’s safe to say we can deduce that a poem presented at a presidential inauguration is going to be patriotic. And Gorman does not disappoint.

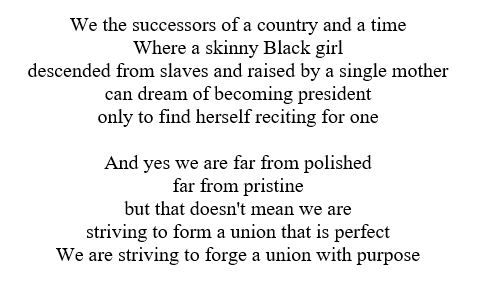

The entire poem has a patriotic tone. Notice how the following lines appeal to our sense of sight to enhance this idea of patriotism.

Gorman gives us a visual description of herself, “a skinny Black girl,” and a description of her personal history (“descended from slaves and raised by a single mother”). This specific example mimics a more universal example. Her poem isn’t just about her personal history and future; it’s about America’s.

Her poem preserves the present, acknowledges the past, and looks forward to the future—everything one would hope for during an inauguration, a new era. Her artwork marks what now is.

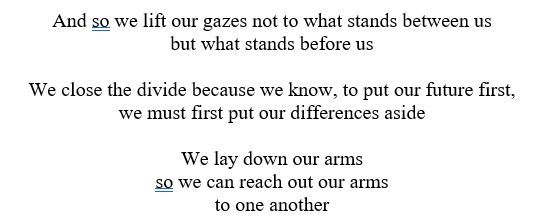

What a great contrast between (and image of) lowering firearms and lifting our physical, literal arms to help one another. This is the message a “skinny Black girl” decided to tell a country that lived through a pandemic, protests and counter protests, and an attack on the US Capitol. This poem encourages healing and unity. Gorman reminds us that we’re not attempting to form “a union that is perfect” but build a “union with purpose.” Two little words (perfect and purpose) that look so similar on a page but have such different meanings, and they are two words I never would have considered comparing if Gorman hadn’t placed them so close together for me.

Because she did, I’m reminded that the US isn’t perfect, and it was never meant to be. That doesn’t mean tomorrow is bleak; it means tomorrow I have purpose. I have hope that the future can be better because I’m going to make it better.

What I hope my students understand, what I hope my parents understand, and what it’s taken me years to understand is that poetry is power. Words create images and sounds that stir feeling: empathy, purpose, drive, love, hope, loss, fear, anger—all of them and more. Poetry allows us to attempt to explain and create our worlds, our own individual ones as well as collective.

What better way to celebrate 2020? What better way to mourn 2020?

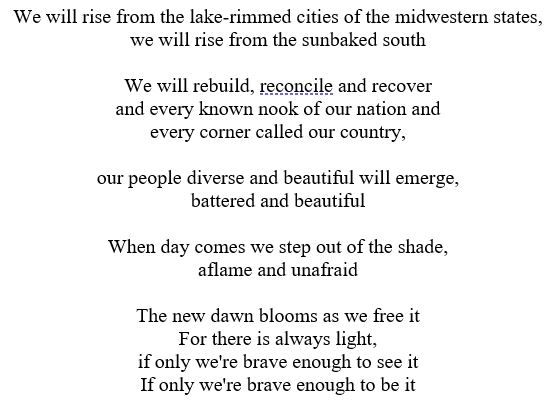

“The Hill We Climb” succeeds at encouraging and uniting. I know it does because after my class of skeptic seventh graders watched Gorman perform her poem, one student raised her hand and said, “I learned poetry can be inspiring.”

My student had a small taste of the power of poetry, and she felt it.

When approaching poetry, my first suggestion was to ignore meaning, the truth is, if you don’t worry about meaning, you usually find it. If you allow yourself to sit with a poem, “waterski across” its surface, listen to it, and just enjoy it, beauty and meaning and depth come. So, for your enjoyment, here’s the end of “The Hill We Climb”:

About the Author: Ranae Rudd is a native of northern Utah, has earned a bachelors in English from Brigham Young University-Idaho and a MFA from Brigham Young University. Currently she is a junior high teacher and loves having the opportunity to teach America's youth. Being a moderate nerd, in her free time Ranae enjoys the finer parts of the Star Wars universe and watching reruns of the Simpsons.